Two Frames of Understanding Jesus

One frame for understanding Jesus is to look at who he chose for disciples.

A few of the guys liked to fish. One of whom was akin to Frank Baum’s cowardly lion. At least one had serious mental ill health (seven demons at that time was code for seriously ill). Rumour had it that another follower was a member of a terrorist organisation, and another sold their body for sex. But then this Jesus group was an itinerant, fringe, co-ed company that attracted rumours. And Jesus, their leader, was rather fringe too.

If you or I were choosing a team to spread our gospel worldwide we wouldn’t have chosen this lot. They consistently didn’t understand what Jesus was saying. Even after his death they still thought it was all about ‘restoring the Kingdom to Israel.’ They wanted to sit on his left and right in glory, not understanding that so-called ‘glory’ would not be power and riches but suffering and heartache. When the heat came on, they disowned him and ran away. The Judas gene was in them all.

The other interesting thing about the disciples is that no one quite knows who they were. It’s a great question for a Sunday School quiz: ‘Name the 12 disciples?’ Matthew’s list includes someone called Thaddeus. Luke’s list excludes him and adds a second Judas. Neither list includes the ‘apostles to the apostles’ Mary Magdalene. Or Mary his mother. Or is it Mary and Martha of Bethany. And then of course the Book of Acts says there are 120 disciples waiting in the upper room.

There are a number of contemporary authors who try to help us understand the marginal nature of Jesus’ disciples. Like Martin Bell’s 1970 image of Rag-Tag Army with ‘soldiers’ wandering off to play with a frog, or walk holding hands. Or James K. Baxter’s The Māori Jesus with disciples that included a housewife who threw her TV in a rubbish bin and an alcoholic priest going slowly mad in a respectable parish. Or Mike Riddell’s 1990s Insatiable Moon with the so-called “loonies” in Bob’s Boarding House in Ponsonby. People on the margins, not skilled managers or qualified leaders by any standards.

The Bible gives us a picture of Jesus’ disciples as people who struggled with life, who tried to be kind and compassionate, who knew failure and misery, and who hoped for a new and different future. These people, simultaneously unremarkable and remarkable, ordinary and extraordinary, were brought together by Jesus and were loved and empowered into change.

The truth is of course that Jesus was an outsider too. And that’s why he was attractive to those who followed him; people who were like him. He was ordinary and extraordinary. One of them, but also (like they were) a child of God.

The other thing is they followed him for a reason. It wasn’t just his charisma, wisdom, or healings. They followed him because of the reality and promise of freedom. And what does freedom look like? It looks like being accepted and loved, freeing one from fear, freeing one to accept and love others. It looks like finding a purpose, finding a group where that purpose makes sense, and slowly becoming your true self.

This idea that religion is about freedom was, and still is, foreign to many religions.

For a religious man Jesus didn’t talk right, act right, or spend enough time the right people. Throughout the following centuries the Church wanted Jesus to primarily reflect the values of a a good and upstanding member of the community. A bit like someone the Letter of Timothy describes as a church minister: blameless, vigilant, sober, a family man, etc.[i]

Jesus the outsider was good news to those relegated to the outside. He disregarded the boundaries that set the respectable and the rejects apart. He ate with the rejected, touched and was touched by the rejected, taught and was taught by the rejected, and healed and was healed by the rejected.[ii] He also suggested that this was how God too would be.

Which is really the nub of the matter.

It is important in Holy Week (the week that begins today and ends at Easter) to remember and restate that Jesus did NOT die for our sins. He died for his so-called ‘sin’ – the crime of sedition against the power of the Empire. He died as a martyr challenging the ‘sin’ of oppressive religion and politics. Jesus’ allegiance was to a different Empire, an upside-down Empire, with an upside-down understanding of God.

So that’s another frame through which we can understand Jesus – namely how he understood power:

Jesus’ power was relational power. In contrast to the more traditional Christian focus on Jesus as God incarnated as a redeemer, theologian Carter Heyward states that 'God was indeed in Jesus just as God is in us- as our Sacred, Sensual Power, deeply infusing our flesh, root of our embodied yearning to reach out to one another'.[iii]This sort of power works to change despair, fear, and apathy to hope, courage, and what Heyward terms 'justice-love'. God (like an energy source) was Jesus' relational power for forging mutual relationships, in which Jesus himself and those around him were empowered to be.

So, each of us can incarnate God (that is, to embody God's power), and that we do so most fully when we seek to relate genuinely to others. When we do this, we could be said to be 'godding'. So human activity can, as theologian Lucy Tatman has observed, be divine activity whenever it is just and loving. In her book Saving Jesus from Those Who Are Right, Heyward asserts that 'the love we make... is God's own love'.

So, today, we are part of a communal effort and struggle to enable the flourishing of love and justice in a world where the potential for relationality is broken, often violently. The project of 'godding', or relationality, is an alternative to a hierarchical understanding of social/relational power, both inside and outside the church.

Most Christian theology and practice assume that God is all-powerful - namely with the resources to initiate, direct, and control whatever he/she desires in order to achieve whatever he/she wishes. This all-powerful God is significantly removed from humanity – especially in terms of power and purity – but wants to be humanity’s friend. There’s an old Sunday School song that captures this sort of God-power: “My God is so big, so strong and so mighty, there’s nothing my God cannot do.”

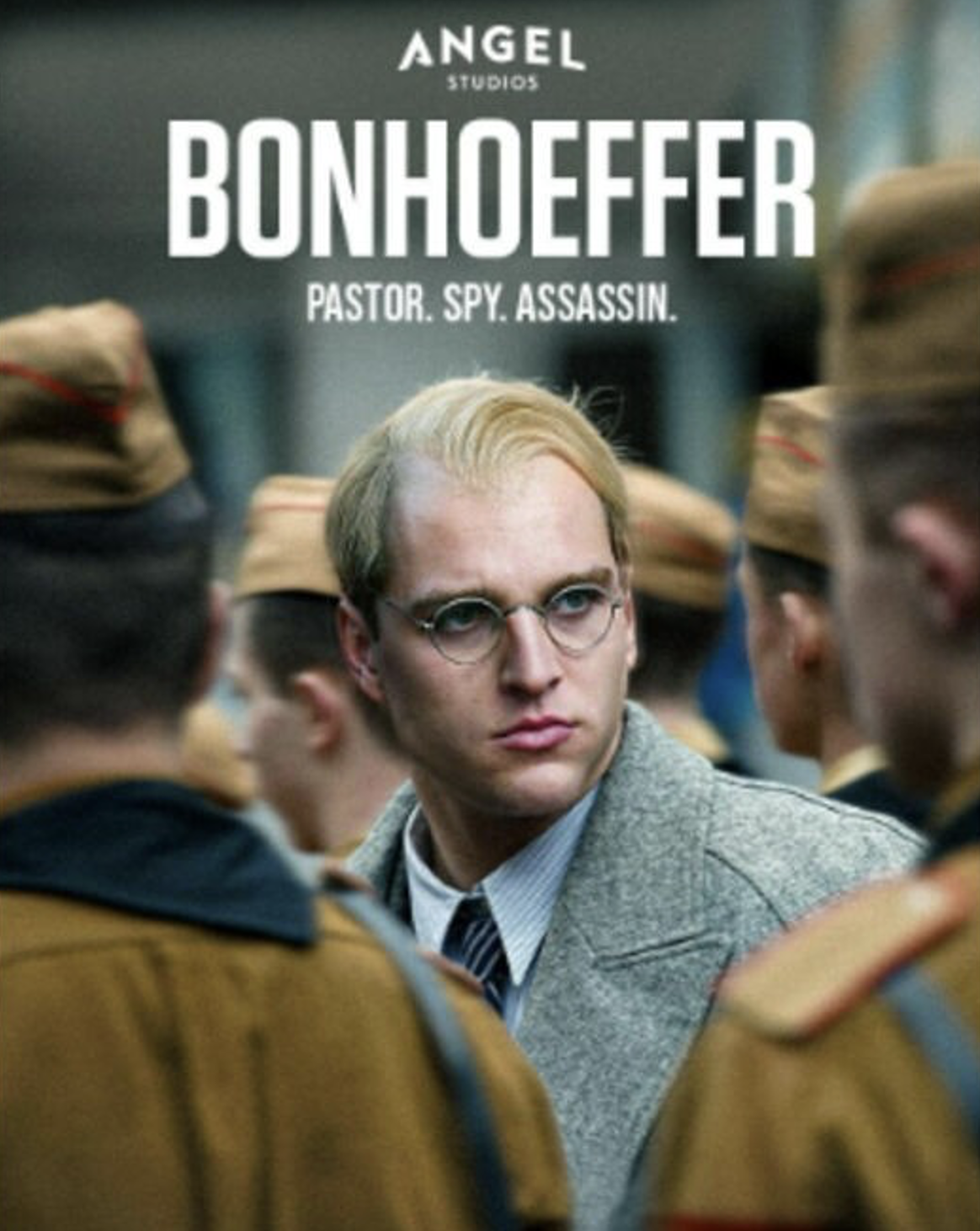

But the cross that Lent is leading us to tells us this is a lie. As Dietrich Bonhoeffer once pointed out, ‘God (is) edged out of the world and onto the cross. God is weak and powerless.’ The cross tells us that suffering could be our experience if we dare to challenge the powerful. The cross tells us that there is no heavenly saviour who will rush down to rescue us. The Sunday School song instead should go something like this: “My God is so small, so weak, and so useless, there’s nothing my God can do.” Not a good sales pitch if you are trying to market religion!

The power of God – and I would posit the only power of God – is that of transformative love, the power of mutual relation. So when the power of love comes up against the power of violent coercion it takes a beating. As Jesus did.

The death of Jesus, and our tradition's insistence that he is the definitive windowframe through which Christians see and understand God, leads us to a place that is essentially heretical: God has no power by which to rule, control or save .God is devoid of this type of power. This is the harsh message of the cross. Like the expendables – the poor, prostitutes, sick, prisoners, and the mentally ill - cast out from places of influence this ‘God' (this antithesis of normative understandings of God) is seen as useless.

The cross therefore is a symbol of uselessness and impotency. It is a symbol of what many fear. And resurrection isn't about getting the power back on, regaining potency and usefulness. God is not that which needs or wants to control - even if we think that an individual or society needs to be controlled.

God is not therefore to be equated with institutions (necessary though they may be for human organisation). God does not crown monarchs, presidents, or prime ministers. Neither does God ordain elders or ministers, nor does God consecrate bishops or archbishops. We do these things; and we do them as best we can. And we hope that something of ‘godding’ will be present in their lives and actions. But it isn't guaranteed.

Not so long ago I would have been branded as a heretic for saying that, and punished accordingly.

As God does not hand out sovereign power, so too God is not a book of rules, or the writer or inspiration for such a book. God is not a Bible, nor is God restricted by what it says.

I believe God is not a power-over being, nor sanctions any power-over relationships. God is not a heavenly controller endorsing any male, or female, controllers on earth. Indeed God is subversive of all our methods of controlling others, using our power to coerce others, and justifying our actions.

Which brings us to the donkey: on Palm Sunday Jesus rode upon a donkey into Jerusalem.

It looked rather silly – his feet almost touching the ground, and maybe the poor animal complaining of back-ache. Not exactly the triumphant-military, adorned-with-armour, riding-a-stallion look. Indeed it was a parody – a subversive parody on controlling, coercive power. The humble donkey was a symbol, both to the biblically literate and to the Roman elite. It symbolized that here was one who had no need for muscular might and the assumptions of the culture of violence. Here was one who was not afraid of seeming to be stupid. Here was one who trusted in a different type of godding foreign to the halls of power. Jesus came as one who would not play the game, who did not have a power-God, but who believed in what his disciples represented – that desire to move from despair, fear, and impotency to acceptance, freedom, and purpose.

[i] I Timothy 3:2-4

[ii] ‘Healed by the rejected’ is how I would interpret the encounter with the Syro-Phoenician woman Mark 7:25-30.

[iii] Heyward, Carter (1999) Saving Jesus from Those Who Are Right:rethinking what it means to be Christian. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress,126.